Sword in the Sky Quake

August/September 634 CE

by Jefferson Williams

Introduction & Summary

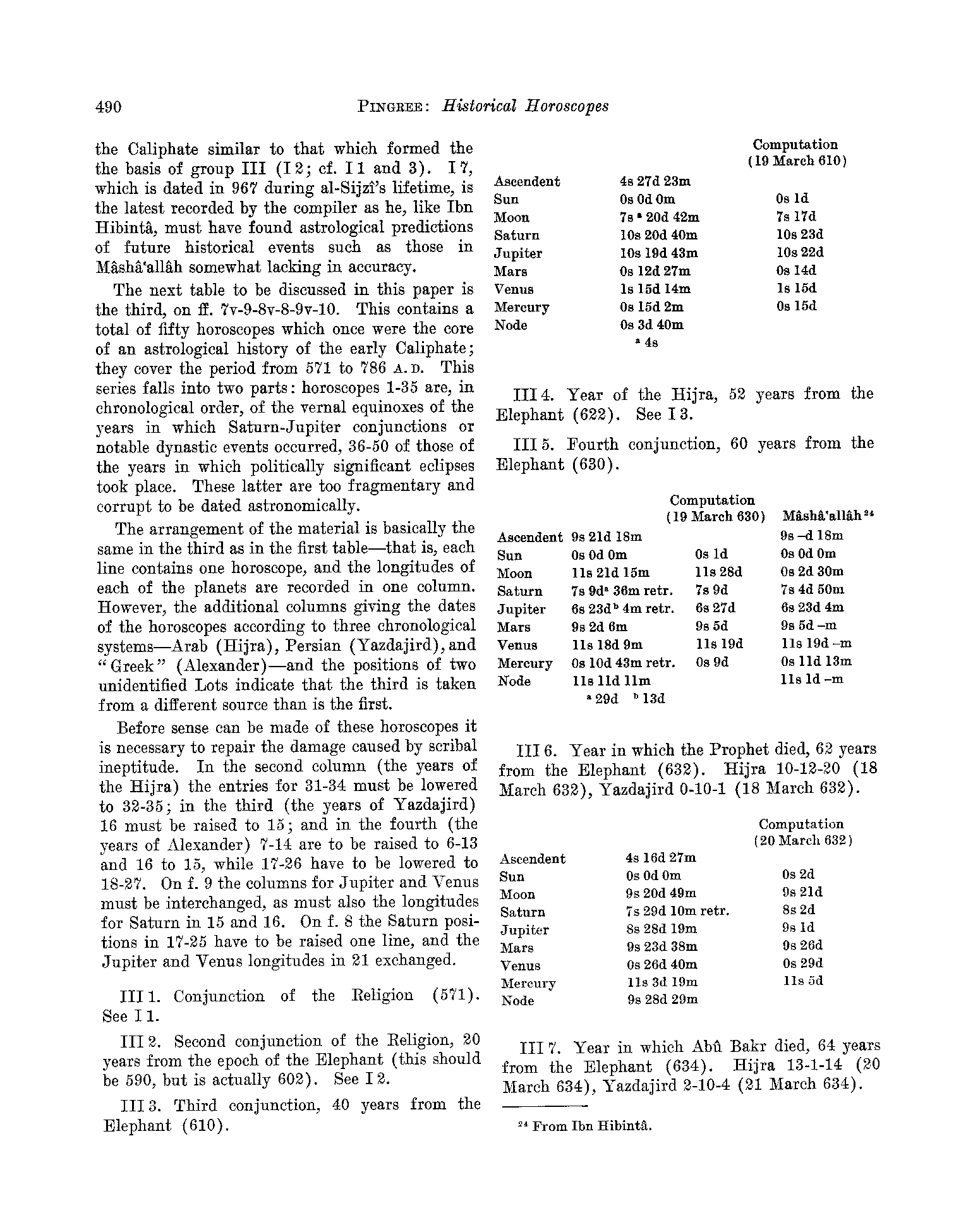

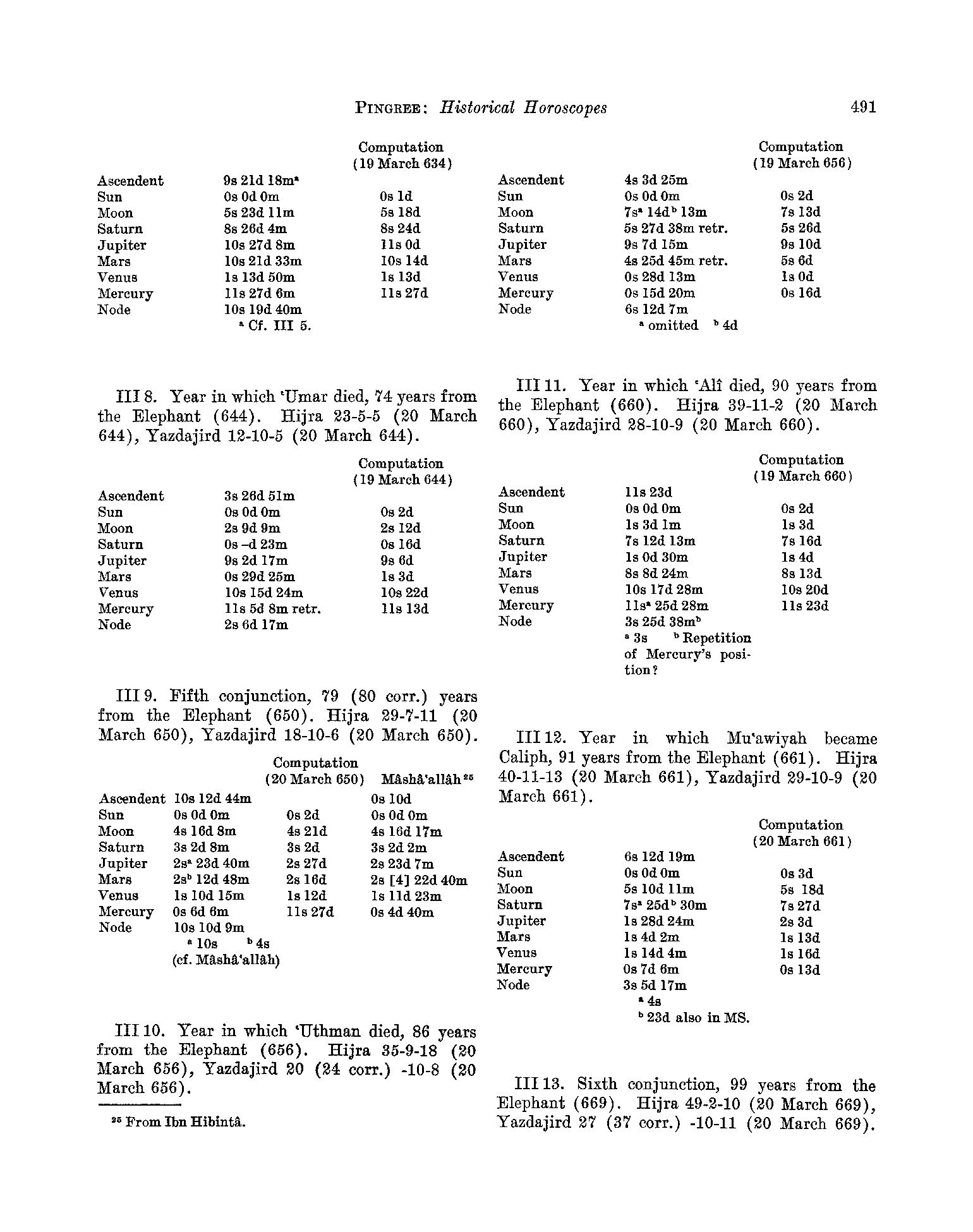

A number of non-contemporaneous sources1 described an earthquake in Palestine around the start of the Muslim conquest of the Levant, a campaign that took place between ~632/633 and 640 CE but for which it is difficult to ascertain the exact dates of the various battles. These same non-contemporaneous sources1 described the earthquake as occurring during the same year or close in time to when the Rashudin Army first successfully invaded and conquered Palestine - i.e. 633/634 CE. A number of authors noted that a celestial apparition was seen in the sky around the same time as the earthquake and/or the Islamic invasion. The apparition was often described as looking like a "Sword in the Sky", lasting for 30 days, and being a portent of the Islamic invasion. Theophanes and his copyist Anastasius Bibliothecarius described it using the Greek term Docetes (δοxίτης). Dall’Olmo (1980:17) writes that Docetes (δοxίτης) is derived from dokion (related: dokos (δοκός)) which means a board or beam and was used by some Byzantine chroniclers to describe a comet. Taken together, these descriptions appear to reference a comet which were often viewed as omens of ruin, pestilence, and the overthrow of kingdoms. If the apparition was a comet, this could date the earthquake to August or September 634 CE when Chinese and Japanese records observed what appears to have been a comet. Two of the authors2 specified that the earthquake struck in September.Textual Evidence

| Text (with hotlink) | Original Language | Biographical Info | Religion | Date of Composition | Location Composed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronicle of Zuqnin by Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre | Syriac |

|

Eastern Christian | 750-775 CE | Zuqnin Monastery | Pseudo-Dionysius did not mention an earthquake but did write that

the stars of the sky fell in such a way that they all shot like arrows toward the northwhich, he wrote, provided the Romans with a terrible premonition of defeat and of the conquest of their territories by the Arabswhile adding that this was in fact what happened to them almost immediately afterwards. The time markers in this specific part of the Chronicle of Zuqnin are frequently inconsistent with known dates of various historical events. |

| Reconstructed Lost Chronicle Of Theophilus of Edessa | Syriac |

|

Chalcedonian Christian | Late 8th century CE | Edessa ?, Baghdad ? |

|

| Ta'rīkh al-Mawṣil by al-Azdi | Arabic |

|

Muslim | late 8th to early 9th centuries CE | Basra ? | This source may mention the celestial apparition. In his translation of the Chronicle of Zuqnin, Harrak (1999:142 n. 4)

compared Syriac text stating that the stars of the sky fell in such a way that they all shot like arrows toward the northto Arabic text in al-Azdi. I was unable to find the corresponding section in al-Azdi from an English translation by Lees (1854) |

| Chronographia Tripartita by Anastasius Bibliothecarius | Latin |

|

Orthodox (Byzantium) | 871-874 CE - accessed an early version of Theophanes | Rome | Accessing an earlier and perhaps more pristine copy of Theophanes' Chronicle, Anastasius,

wrote that in the 24th year of Heraclius there was another earthquake in Palestineand a sign appeared in the southern sky, something known as docetes, announcing the coming of Arab rule. It remained for thirty days extending from south to north in the shape of a sword.. Specific instances of damage or cities that were affected was not mentioned. While Anastasius states that this happened in the in the 24th year of Heraclius, in the extant version of Theophanes currently available, this event was dated to the 23rd year of Heraclius. Anastasius' date (5 Oct. 633 to 4 Oct. 634 CE - 24th year of Heraclius) is more compatible with the comet reports from China and Japan. |

| Chronicle of Theophanes | Greek |

|

Orthodox (Byzantium) | 810-814 CE | Vicinity of Constantinople | Theophanes wrote that an earthquake occurred in Palestineand there appeared a sign in the heavens called dokites in the direction of the south, foreboding the Arab conquest. It remained for thirty days, moving from south to north, and was sword-shaped. Specific instances of damage or cities that were affected was not mentioned. In typical fashion Theophanes provided a variety of not entirely consistent chronological markers but the earthquake appears to be approximately synchronous with the Muslim conquest of the Levant commonly thought to have begun in A.H. 13 (7 March 634 - 24 Feb. 635 CE) although Donner (2014) in his book The Early Islamic Conqueststhinks it more likely that they began in A.H. 12 (18 March 633 - 6 March 634 CE). |

| Chronicle of Seert | Arabic |

|

Nestorian Christian | probably between 907 and 1020 CE | The Chronicle of Seert does not mention an

earthquake but does say that there appeared in the sky something like a lance from south to north and then it extended from east to west, and it remained thus for 35 nights. |

|

| Book of History by Agapius of Menbij | Arabic |

|

Melkite | 10th century CE | Manbij, Northern Syria | Agapius of Menbij mentions an earthquake twice in two separate passages

separated by a few sentences. In the first passage he wrote that in this year there was a violent earthquake, and the sun was darkened. It is unclear from the text what year "this year" refers to. In the second passage, Agapius wrote that in year 3 of Abu Bakr, there was a violent earthquake in Palestineand for thirty days the ground trembled. Immediately following this earthquake description, Agapius wrote that Abu Bakr died (23 Aug. 634 CE). Depending how one choses to interpret the 3rd year of Abu Bakr, the second passage could lead to dates from 8 June 634 to 7 June 635 CE or from 8 June 634 to 23 Aug. 634 CE. |

| Synopsis Historion by Cedrenus | Greek |

|

Orthodox (Byzantium) | late 11th or early 12th century CE | Anatolia | Cedrenus does not mention an earthquake but wrote that after

Muhammad's death (8 June 632 CE) a comet appeared which lasted for 30 days extending from south to north, looking like a sword. Cedrenus may have dated this to the 23rd year of Heraclius (5 Oct. 632 to 4 Oct. 633 CE). |

| Chronicle by Michael the Syrian | Syriac |

|

Syriac Orthodox Church | late 12th century CE | Probably at the Monastery of Mar Bar Sauma near Tegenkar, Turkey | Michael wrote about the earthquake twice in two separate passages specifying two

different dates. In the first passage he described a violent earthquakewhich he dated to September 634 CE. After the earthquake there was a sign in the sky; it appeared in the form of a sword stretching from south to north, and remained for thirty days. To many it seemed to signify the coming of the Taiyayz (Arabs). Specific instances of damage or cities that were affected was not mentioned. In the second passage he described a great earthquakein A.G. 946 (1 Oct. 634 to 30 Sept. 635 CE). At the moment of the earthquake the sun was eclipsed. Although, in his second passage, he mentioned damage to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre due to this earthquake, this was a false synchronicity. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was damaged or destroyed in 614 CE during the Sasanian conquest of Jerusalem. It was restored in 629 CE by Modestus and was intact when Omar took possession of Jerusalem in 637 CE (Le Strange, 1890:202). So, specific instances of damage or cities that were affected was effectively not mentioned in the second passage as well. |

| The Blessed Collection by George al-Makin | Arabic |

|

Coptic Christian | 1262-1268 CE | Damascus (parts may have also been written in Cairo) | al-Makin wrote about the earthquake in two separate but

virtually identical passages stating in both that there was a great earthquake in Palestinewhich lasted for 30 days. There is no mention of celestial apparitions in either passage. |

| Chronicon by Bar Hebraeus | Syriac |

|

Syriac Orthodox Church | 13th century CE | Jazira ? Persia ? | Bar Hebraeus wrote that at this time, in the month of ilul (September), an earthquake took place. And a sign, like unto a spear, appeared in the heavens, and it reached from the south to the north, and it remained there for thirty days. It is unclear what time "at this time" refers to. Other chronological clues in the text may date the earthquake to between 8 June 632 and 23 Aug. 634 CE. |

| The History of the Caliphs by Jalal al-Din As-Suyuti | Arabic |

|

Muslim | 15th century CE | Cairo | al-Suyuti wrote in his book The History of the Caliphs that an earthquake was experienced in Mecca after Muhammad died on 8 June 632 CE and after Abu Bakr died on 23 August 634 CE. Both earthquake reports may be theologically motivated. |

| Annals by Eutychius | Arabic |

|

Melkite | 1st half of 10th century CE | Alexandria, Egypt | Background information on the Muslim conquest of the Levant. There is no apparent mention of the earthquake or a celestial apparition but there is material about the battle in Gaza. |

| Chronicle Ad 724 | Syriac |

|

Christian | Background information - contains a list of the reigns of the early Caliphs apparently sourced from an original Muslim document. Abu Bakr's reign is listed as lasting 2 years and 6 months (in the lunar Islamic calendar). | ||

| The History by Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-Yaʿqūbī | Arabic |

|

Muslim - thought to have had Shi'ite sympathies | Late 9th or early 10th century CE | Cairo ? | Background information - al-Yaqubiʾ dated the death of Abu Bakr to Tuesday 21 Jumādā II A.H. 13 (22 or 23 August 634 CE). |

| History of the Prophets and Kings by al-Tabari | Arabic |

|

Muslim | ~915 CE | Baghdad | Background information - al-Tabari dated the death of Abu Bakr to Monday 21 Jumādā II A.H. 13 (22 August 634 CE). |

| Nectarius of Jerusalem | Greek |

|

Greek Orthodox Christian | before 1680 CE | Jerusalem ? | Nectarius of Jerusalem (aka Patriarch Nektarios) wrote in Part Δ of his Epitome that

in A.H. 13 (7 March 634 - 24 February 635 CE),

a great earthquake happened in Palestine, which lasted for thirty days. This passage may have been sourced from Al-Makin. In a separate passage, Nectarius also wrote about a beam shaped comet appearing in the sky but dated this to after the death of Mohammad on 8 June 632 CE. |

| Comet | Kronk (1999) reports that

the Chinese texts Chiu T'ang shu (945), T'ang hui yao (961), and Hsin T'ang shu (1060)state that a "sparkling star" was seen on 634 September 20which disappeared after 11 days of visibility, or on about September 30. Kronk (1999) reports that the Japanese text Nihongi (720) says a "long-tailed star"was seen in the south from 29 Aug. - 27 Sept 634 CE and that the people of the time called it a "besom-star". The text adds that sometime during the month of 635 January 24 to February 22 "the besom-star went round and was seen in the east.". These observations agree with the catalog of Ho Peng Yoke (1962) used by Ambraseys (2009) and Guidoboni et al. (1994). The observations also suggest that the "sword in the sky" described in the Near Eastern sources was probably a comet and was probably the same comet observed in Chinese and Japanese sources. |

|||||

| Eclipse Paths | In his 2nd passage, Michael the Syrian

reported that the sun was eclipsed at the same time that there was an earthquake.

Agapius of Menbij reported that after Muhammad died there was a a violent earthquake, and the sun was darkened. Observable Eclipses in the region occurred on 12 Feb. 634 CE, 1 June 634 CE, and 19 Aug. 635 CE. |

|||||

| Celestial Sightings Summary | ||||||

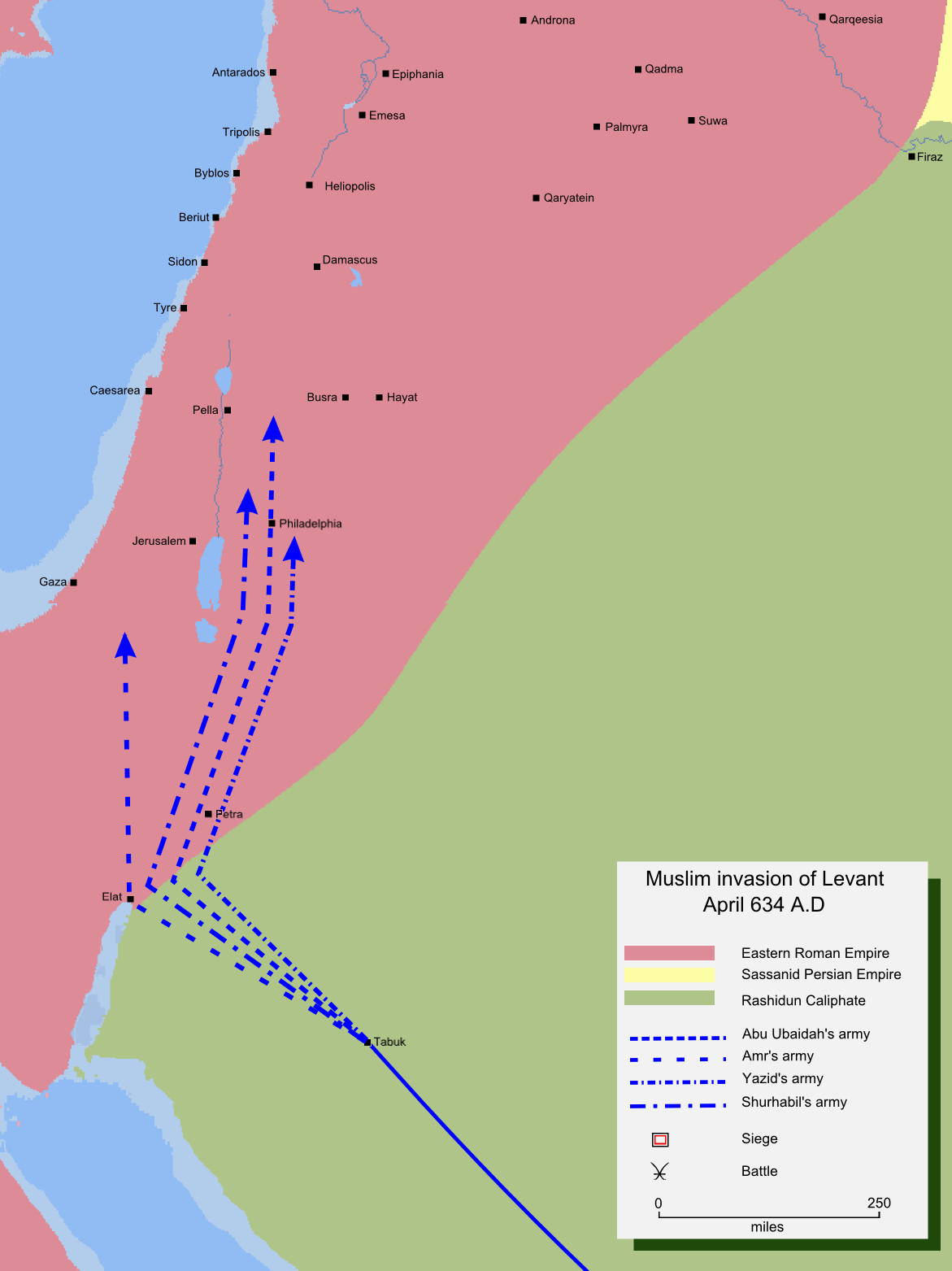

| Islamic Conquests |

|

|||||

| Source Commentary | ||||||

| Text (with hotlink) | Original Language | Biographical Info | Religion | Date of Composition | Location Composed | Notes |

Archaeoseismic Evidence

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qasr Tilah | possible |

Haynes et al. (2006) examined paleoseismic and archeoseismic evidence related to damage to

a late Byzantine—Early

Umayyad birkeh (water reservoir) and aqueduct at

Qasr Tilah and concluded that left lateral slip generated by several earthquakes cut through a corner of the

reservoir and aqueduct creating displacement of the structures. They identified 4 seismic events

which produced coseismic slip on the Wadi Arava fault and led to a lateral displacement of 2.2. +/- 0.5 m at the

northwest corner of the reservoir (aka birkeh) and 1.6 +/- 0.4 m of the aqueduct. The first seismic event was dated to

the 7th century. Haynes at al (2006) suggested it was caused by either the

Sword in the Sky Quake (633/634 CE) or the

Jordan Valley Quake of 659/660 AD -

favoring the Jordan Valley Quake. There was a repair after this 7th century destruction indicating that the site

was occupied when the earthquake struck. Because of the repair,

it is unclear how much lateral slip was produced (or even if there was lateral slip ?). At some point the site was abandoned.

Haynes et al (2006) noted that archeological evidence at the site indicates that it was abandoned and was not occupied

past the Early Umayyad Period (661-700 CE). They also noted that

MacDonald (1992) [] collected some Byzantine and Umayyad surface potsherds at the site and documented ruins of Byzantine houses (village) along the fan surface of Wadi Tilah.If the repair fixed a problem caused by lateral slip rather than generalized destructive shaking, the slip would indicate that part of the Araba fault broke during this event. |

|

| Petra - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Petra - Petra Theater | possible | Jones (2021:3 Table 1) reports a second

potential seismic destruction of the Theater in Phase VII noting that the Phase VII destruction of the Main Theatre is difficult to date, as the structure had gone out of use long before.Jones (2021:3 Table 1) suggested the late 6th century earthquake ( Inscription at Areopolis Quake) or the mid-8th century earthquake (e.g. earthquakes observed in the Qatar Trench in the South Araba by Klinger et al, 2015) as candidates. |

|

| Petra - Jabal Harun | possible | ≥ 6 | Phase 6 destruction was dated to the 1st half of the 7th century CE by Mikkola et al (2008). Destruction was inferred based on rebuilding evidence in Phase 7. No unambiguous and clearly dated evidence of seismic damage was found. Mikkola et al (2008) also noted a change in liturgy in Phase 7 which could have also been at least partly responsible for the rebuild. |

| Petra - The Petra Church | possible | ≥ 8 | Fiema et al (2001) characterized structural destruction of the church in Phase X as likely caused by an

earthquake with a date that is not easy to determine. A very general terminus post quemof the early 7th century CE was provided. Destruction due to a second earthquake was identified in Phase XIIA which was dated from late Umayyad to early Ottoman. Taken together this suggests that the first earthquake struck in the 7th or 8th century CE and the second struck between the 8th and 16th or 17th century CE. |

| Bet Sh 'ean | possible | Tsafrir and Foerster (1997:143-144) dated a seismic destruction event to the 7th century CE.

The event caused the destruction of Silvanus Hall; all the columns in the southwest part of the hall were found collapsed in the same direction, in a way that leaves no doubt about the cause of the destruction.They suggested it was likely that the same earthquake caused the collapse of the porticoes of the Byzantine agora, the portico of the sigma, and most probably the columns of Palladius Street. |

|

| Jerash - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Jerash - Umayyad House | possible | Gawlikowski (1992:358)

reports that the Umayyad house was built on level ground after an earthquake.Construction was well dated by the numismatic findings. Earthquake destruction is inferred based on rebuilding evidence. |

|

| Jerash - Macellum | probable | ≥ 8 |

Uscatescu and Marot (2000:283) dated seismic destruction of the Macellum to at the latest to the second quarter of the seventh centurybased on pottery and coins. The seismic destruction layer was found in a sealed and undisturbed context and is well-dated. Uscatescu and Marot (2000:281) report extensive destruction [] well evidenced by the fallen vaulted and tiled roofs and collapsed walls; a huge collapse that reaches a thickness of more than two and a half metres,and was composed by voussoirs, tiles, ashlars, architraves, column shafts, capitals and other architectonic elements. |

| Jerash - Temple of Zeus | possible | ≥ 8 | Rasson and Seigne (1989) reported on excavations of a cistern at the Temple of Zeus.

Two seismic destruction events were interpreted from the excavation - one in the 7th century CE and another in the 8th.

The 1st seismic event was manifest in partial roof collapse. Ceramics beneath the collapse layer dated to the Umayyad period and suggested an earthquake

Which struck in the middle of the 7th century CE. Gawlikowski (1992:358) reports

further 7th century CE archaeoseismic evidence in a vaulted corridor of the lower terrace where a herd of goats was buried along with a kid goat.

According to Gawlikowski (1992:358), the age of a kid indicates that the cataclysm took place in May-June and moreover a Byzantine currency with an Arab countermark indicating the beginning of Muslim government (Seigne, unpublished report of 1984, kindly communicated by the author).This would suggest that the 1st earthquake was the one of the Jordan Valley Quake(s). |

| Jerash - Hippodrome | possible | ≥ 8 | Ostrasz and Kehrberg-Ostrasz (2020:4) report that

the masonry of most of the building collapsedwith only the carceres and the south-east part of the caveasurviving. Archaeological evidence seems to constrain the date of this earthquake to the 6th to 7th centuries CE. |

| Heshbon | possible | ≥ 8 | Walker and LaBianca (2003:453-454) uncovered

7th century CE archeoseismic evidence which they attributed to the Jordan Valley Quake of 659/660 CE from an excavation of an Umayyad-period

building in Field N of Tall Hesban. They report a badly broken hard packed yellowish clay floor which was

pocketed in places by wall collapse and accompanied by crushed storage jars, basins, and

cookware. Storage jars and basins and cookware were dated in the field to the transitional Byzantine-Umayyad period. |

| Tell es-Samak/Tel Shiqmona | possible to unlikely | ≥ 7 | 7th century CE Earthquake (?) - Barzilay (2012) interpreted flexed stone structures as a consequence of a 7th century CE earthquake and estimated a local site Intensity of VII or higher. Excavator Hagit Torge (personal communication, 2021) attributed the deformations to the active clay soil. Taxel (2013:79-80) also cast doubt on the possibility that the site was damaged by an earthquake leading to it's abandonment. The Deformation Map shows that the displaced walls are due to vertical uplift and suggest an expansive active soil as the cause. If an earthquake caused the chaotic deformation patterns shown in the map, the site would have to have been above the hypocenter of a powerful earthquake which seems unlikely. If this was the case, more extensive deformation and collapse would be expected form this site and nearby sites and the local Intensity would have been IX (9) or higher. Thus, I agree with Hagit Torge (personal communication, 2021) and Taxel (2013:79-80) that a seismic origin for the observed deformations is not likely. |

| Pella | possible | Blanke and Walmsley (2022) and Walmsley (2007) described extensive archaeoseismic evidence, some of which appears to be based on rebuilding evidence, for a 7th century CE earthquake at Pella. The Battle of Fahl (aka Pella) was fought near Pella around 634 or 635 CE. | |

| Monastery of Euthymius | possible | ≥ 8 | Hirschfeld (1993:354) inferred

that the monastery was destroyed by a 7th century earthquake based on rebuilding evidence. Reconstruction was dated to the 2nd half of the 7th century

apparently based on the early Muslim period style of construction. The Maronite Chronicle states that the Monastery of Euthymius was destroyed by

an earthquake in A.G. 971 (660-661 CE) along with the dwellings of many monks and solitaries. See Textual Evidence section for more details. |

| Monastery of Khirbet es-Suyyagh | possible | ≥ 8 | 7th century CE Earthquake(s) - Taxel et al (2009) surmised

that Phase IIA ended with an earthquake and established a terminus post quem of 629/630 CE for repairs to damaged parts of the monastery at the start of Phase IIB.

This was based on a 629/630 CE coin found below the mosaic floor in the northern aisle of the church (Locus 387) attributed to Phase IIB. Another coin of Constans II (641-648 CE) was found in the fill that covered the corridor north of the main gate (Locus 281)however it was noted that this fill could also be related to the construction of the blocking wall of the corridor in Phase III. Pottery found below the fieldstone paving which abutted on the new (southern) storeroom in the external courtyard and to the repaired doorway of the subsidiary gate (Loci 181 and 183)was dated to the mid-late 7th century. Lack of fire evidence and evidence of archaeoseismic damage led Taxel et al (2009) to conclude that observed damage and repairs of damage was probably due to an earthquake(s) although destruction due to Persian and, later on, Muslim military activity could not be entirely ruled out. |

| Caesarea | possible | ≥ 8 | mid-7th century CE Earthquake - According to Raban et al. (1993 v. I:64), Vault 2 in Area CV collapsed

suddenly, crushing pottery vessels that had been resting on the floors. The destruction was dated to the mid-7th century CE, with

researchers attributing the collapse to seismic activity. This dating was based on ceramics and coins, the most recent of which

belonged to the reign of Heraclius [r. 610-641 CE]. Two possible earthquake events were suggested as causes: the ~634 CE Sword in the Sky Quake and the 659/660 CE Jordan Valley Quake(s). Raban et al. (1993 v. I:64) reported that Vault 2 was a two-story structure that collapsed downward, with its arcade falling downward and westward. Additionally, evidence suggested that the second-story floor had flipped over during the event. |

| Khirbet al-Niʿana | possible |

Taxel (2013:178-179) noted the following about archaeoseismic evidence in Khirbet al-Niʿana

Excavation of the western fringes of the inhabited area (the results of which were only preliminarily published) show no clear evidence for occupation after the mid-seventh century. According to the excavator (Torge, 2010)The site was largely abandoned at the beginning of the Umayyad period and most of the masonry stones were plundered. The signs of destruction and burning may point to its destruction in the earthquake of 633 CE.Unfortunately, however, the basis for this dating was not provided in the report. |

|

| Mount Nebo | needs investigation | ||

| Ein Hanasiv | possible | ≥ 8 | Karcz et. al. (1977) list archeoseismic evidence (oriented collapse, alignment of fallen masonry) in Ein Hanasiv in the 7th century AD based on Vitto (1975). |

| Giv’ati Junction | possible | ≥ 7 | Baumgarten (2001) excavated a round pottery kiln at Giv'ati Junction dated to the

4th-7th century CE (Shmueli, 2013).

Langgut et al (2015) report that four fired Late Roman Amphora (similar to those at Yavne) "were found inside the

kiln’s collapsed firing chamber" covered by a thick layer of aeolian sand. Langgut et al (2015) noted that while "the excavator

suggested that the kiln was destroyed during operation, possibly due to some technical fault, and was consequently abandoned (Baumgarten 2001)",

Langgut et al (2015) believe an earthquake should also be considered as a cause of destruction. Shmueli (2013) excavated Stratum III in a rectangular building (L109, L119) at Giv'ti Junction in 2011 where, on the floor, they found three Gaza jars which were set upside down (Fig. 4) and broken. A fourth jar was found upright but also broken. Based on numismatic finds, they dated the beginning of the settlement to the fourth or fifth century CE. Construction and use of the rectangular building was dated to the fifth to seventh centuries CE. In the seventh century the installation and building went out of use. |

| Ashdod-yam | possible | Post 600 CE Earthquake -

Di Segni et al. (2022:439-440) reported on excavations of a Byzantine Church at Ashdod-Yam. The

church was constructed in the late 4th or beginning of the 5th century CE, at the latest. They found that all uncovered parts of the complex yielded clear signs of destruction by fire, sealed by a burned layer of collapse, consisting of a large quantity of shattered roof tiles and wooden beams (Figs. 21-22). Numismatic evidence indicates that this destruction occurred around 600 CE, or perhaps slightly later. Prior to destruction, Di Segni et al. (2022:440) suggest that the church was abandoned in a planned manner. After the destruction, the church was subject to the systematic removal of usable stones and marble columns. A few possible traces of an earthquake that occurred after the abandonment and destruction of the churchwere also identified. |

|

| Avdat/Oboda | possible | ≥ 8 | 7th century Earthquake - A terminus post quem for a 7th century CE earthquake was established from the latest inscription found at the site in the Martyrion of St. Theodore (South Church) in 617 CE (Negev 1981: 37)(Erickson-Gini, 2014). Erickson-Gini (2014) noted that there was massive destruction evident throughout the site, and particularly along the western face of the site with its extensive caves and buildings (Korjenkov et al., 1996).Korzhenkov and Mazor (1999) uncovered extensive archeoseismic effects from the earthquake and estimated an Intensity of 9 - 10, posited that destruction was caused by a compressional seismic wave, and located the epicenter SSW of Avdat somewhere in central Negev. Discontinuous Deformation Analysis of the bulges in the Roman Tower of Avdat by Kamai and Hatzor (2005) leads to an Intensity Estimate of 8 - 10. A Ridge Effect is likely present at Avdat |

| Mizpe Shivta | possible | Erickson-Gini (personal correspondence, 2021) relates that this site in the Negev suffered seismic damage in the 7th century CE - sometime after 620 CE. | |

| Mezad Yeruham | possible | Erickson-Gini (personal correspondence, 2021) relates that this site in the Negev suffered seismic damage in the 7th century CE - sometime after 620 CE. | |

| Shivta | possible | ≥ 8 | Late Byzantine Earthquake - Early 7th century CE ? -

Erickson-Gini (2013) suggested that a revetment wall outside Room 123 was evidence of a Late

Byzantine earthquake

Revetment walls present around the North Church and buttressing the western wall of Building 123 (Hirschfeld 2003 - see highlighted site plan above) are indications that some damage to the site took place in the Late Byzantine period, probably in the early seventh century CE when the neighboring site of ‘Avdat/Oboda was destroyed in a tremendous earthquake.A site effect at Shivta is unlikely due to a hard carbonate bedrock. Korzhenkov and Mazor (1999a) estimate Intensity of 8 -9 with the epicenter a few tens of km. away and to the WSW |

| Rehovot ba Negev | possible | ≥ 8 | "The Byzantine Shock" - 7th century CE - Korzhenkov and Mazor (2014) identified an earthquake which they beleive struck in the 7th century CE. Rehovot ba Negev appears to be built on weak ground. There is a probable site effect present as much but not all of Rehovot Ba Negev was built on weak ground (confirmed by A. Korzhenkov, personal communication, 2021). Korzhenkov and Mazor (2014) estimated an Intensity of 8-9 with an epicenter to ESE. |

| Saadon | possible | ≥ 7 | Phase 2 Earthquake - mid-7th century CE -

Erickson-Gini (2018) reports that The [Southwestern] church was heavily damaged and subsequently repaired in the mid-7th century CE and continued to be used for several years in the Umayyad period (mid-7th - 8th centuries CE). A `wine-press' hewn along the bedrock shelf on the northeast bank of Nahal Sa'adon was apparently broken by the same seismic event.Damage observations reveal that walls aligned in a WNW direction were damaged. |

| Nessana | possible | Erickson-Gini (personal correspondence, 2021) relates that Nessana suffered seismic damage in the 7th century CE - sometime after 620 CE. | |

| Mamphis | possible | ≥ 8 | The 2nd earthquake at Mampsis suffers from dating ambiguities and a chronological debate between Negev (1974:412, 1988) and Magness (2003). Considering all possibilities of this debate leads to a date between the 5th and 7th centuries CE. Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) estimated an Intensity of 9 or more with an epicenter to the SW. |

| Haluza | possible | ≥ 8 | Second earthquake.

Korjenkov and and Mazor (2005) discussed chronology of the second earthquake.

The Early Arab – Second Ancient EarthquakeKorjenkov and and Mazor (2005) noted that while the Sword in the Sky Quake of 634 CE destroyed Avdat 44and ruined other ancient towns of the Negev 45, archeological data demonstrate that occupation of the [Haluza] continued until at least the first half of the 8th cent. A.D.46. This led them to conclude that one of the mid 8th century CE earthquakes was a more likely candidate. Unfortunately, it appears that we don't have a reliable terminus ante quem for the second earthquake. Korzhenkov and Mazor (1999a) estimated a minimum Intensity of 8-9 with an epicenter a few tens of kilometers away and an epicentral direction to the NE or SW - most likely to the NE |

| Aqaba/Eilat - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Aqaba/Eilat - Aila | possible | 7 |

Thomas et al (2007) identified earthquake destruction (Earthquake IV) in a collapse layer which they suggested struck in the early to middle 7th century CE.

The pottery constrains the date of Earthquake IV to sometime between the seventh century and the mid seventh to eighth century. In this case, an early to middle seventh-century date would best fit the dating evidence. |

| Castellum of Qasr Bshir | possible | ≥ 8 |

Clark (1987) identified a tumble layer which could have been caused by an earthquake or gradual decay.

In H.1 a 0.25 m deposit of rock tumble and windblown loess (H.1:010 and 011) overlay the Early Byzantine I-II occupational deposits. This appears to represent a period of abandonment and of building collapse.Clark (1987) found the tumble in the in Post Stratum III gap which he bracketed to between ca. 500 and 636 CE" |

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |

Tsunamogenic Evidence

Paleoseismic Evidence

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| al-Harif Syria | possible | ≥ 7 | Sbeinati et al (2010)

state that Event Y, characterized from paleoseismology, appears to be older than A.D. 650–810 (unit d, trench A) and younger than A.D. 540–650 (unit d3 in trench C). The results of archaeoseismic investigations indicate that ages of CS-1 (A.D. 650–780) and tufa accumulation CS-3-3 (A.D. 639–883) postdate event Y.Combined together, this constrains Event Y to 540-780 CE. |

| Bet Zayda | possible | ≥ 7 | Wechsler at al. (2014) may have seen evidence for this earthquake as Event CH3-E1 (Modeled Age 662-757 CE). Event CH2-E1, which struck next (Modeled Age 675-801 CE), appears to correlate with the Holy Desert Quake of the Sabbatical Year Earthquake sequence. |

| Dead Sea - Seismite Types | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Dead Sea - ICDP Core 5017-1 | possible | 7 | Lu et al (2020) associated a turbidite in the core to a middle 8th century earthquake. CalBP is reported as 1248 ± 44 yr B.P. This works out to a date of 702 CE with a 1σ bound of 658 - 746 CE indicating that the Jordan Valley Quake, Sword in the Sky Quake, and the Sabbatical Year Quakes are all possibilities. Ages come from Kitagawa et al (2017). The deposit is described as a 16.5 cm. thick turbidite (MMD). Lu et al (2020) estimated local seismic intensity of VII which they converted to Peak Horizontal Ground Acceleration (PGA) of 0.18 g. Dr. Yin Lu (personal correspondence, 2021) relates that "this estimate was based on previous studies of turbidites around the world (thickness vs. MMI)" ( Moernaut et al (2014). The turbidite was identified in the depocenter composite core 5017-1 (Holes A-H). |

| Dead Sea - En Feshka | probable | 5.6-6.4 | Kagan et. al. (2011) assigned a 634 AD date [648 AD ± 45 (±1σ) - 633 AD ± 95 (±2σ)] to a 1 cm . thick Type D [Folded laminae - i.e. Linear Wave (Type 1) of Wetzler et al (2010)] seismite at a depth of 172.0 cm.. |

| Dead Sea - En Gedi | possible | 5.6-6.3 | Migowski et. al. (2004) did not assign a date of 634 AD to any of the seismites in the En Gedi Core (DSEn) but did assign a 0.5 thick seismite at a depth of 1.99 m to a date of 660 AD. |

| Dead Sea - Nahal Ze 'elim | no evidence | At site ZA-2, Kagan et. al. (2011) did not assign any seismites to a date of ~634 AD. No seismites in her section have a modeled age which overlaps with a 634 AD date (± 1σ or ± 2σ). | |

| Araba - Introduction | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Araba - Taybeh Trench | possible | ≥ 7 | LeFevre et al. (2018) might have seen evidence for this earthquake in the Taybeh Trench (Event E3 - Modeled Age 551 AD ± 264). |

| Araba - Qatar Trench | no evidence | ≥ 7 | The Sword in the Sky Quake is just outside the modeled ages for Events E4 (758 CE ± 87), E5 (758 CE ± 87), and E6 (251 CE ± 251) (Klinger et. al., 2015). |

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |